Dinner and a seminar on Ethiopian cuisine and culture, with a welcoming coffee ceremony, and time to talk

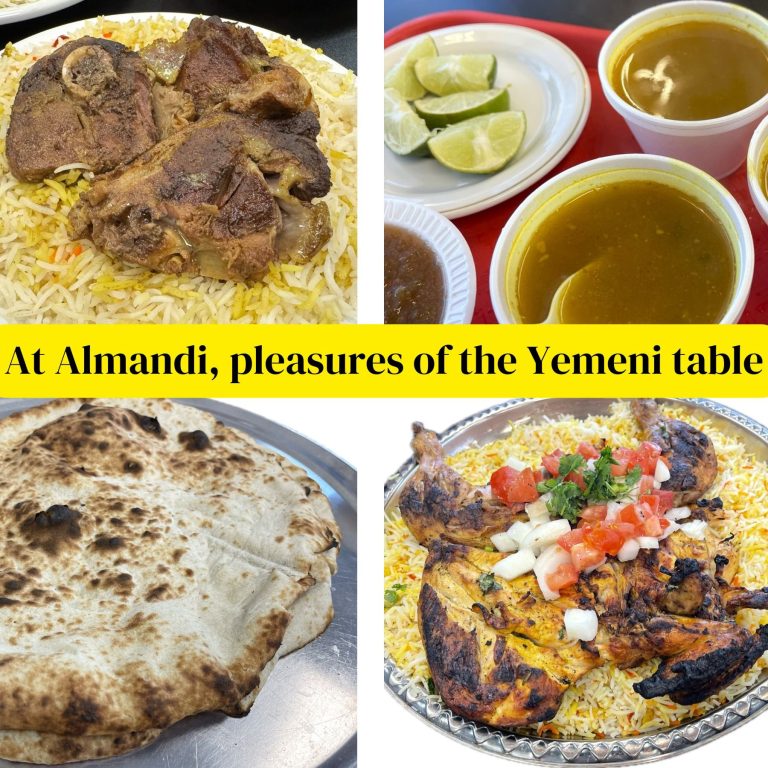

Zelalem Gemmeda honed her restaurateur skills running a restaurant in an Ethiopian refugee camp in Yemen. It was never easy handling business in a male-dominated culture, but she found a way.

Driven to earn enough to send her son Solomon to English lessons, she handled business for three years before her family could come to the United States. Soon after arrival, Solomon took the Park School entrance exam, and got a full scholarship. After graduating from Colgate University with a bachelor’s in neuroscience, he’s working in DC.

She was a 17-year-old Addis Ababa high schooler when her father’s imprisonment cut off her dream of a college education. Now she and husband Gezaghne Derseh have gotten Solomon launched, and daughter Feben is working on her graduate degree.

“I couldn’t get that chance,” Gemmeda said. “So when I get this chance, I have to work hard for that.”

Since 2011, while other Buffalo Ethiopian restaurants opened and closed, Zelalem Gemmeda’s Abyssinian Ethiopian Cuisine never stopped feeding the community’s need for doro wot, kik alicha, and yabeha gomen.

Not just to fellow Ethiopians, but the growing number of native Western New Yorkers who’ve learned that chicken and hardboiled egg braised in caramelized onion gravy (doro wot), yellow split peas (kik alesha), and spinach simmered with spices (yabeha gomen) are pretty darn tasty.

Gemmeda’s cooking will center Ethiopian 101, dinner with a seminar, set for 5 p.m. May 21 at Downtown Bazaar, 617 Main St. Doro wot, beef tibs (sauteed spiced beef), misir wot (red lentils), kik alicha, and yaheba gomen, plus a welcoming coffee ceremony administered by Gemmeda herself. Tickets, $35, available here.

In between, I’ll fill you in on the history and practice of Ethiopian cuisine, strongly influenced by its ancient Christian culture.

Since every dish tastes better with backstory, I sat down with Gemmeda to ask how she got to the Downtown Bazaar.

Gemmeda’s father, a government official, was jailed when she was 17, and would die in prison. Holding two degrees, from an Italy college and the University of Michigan, her father had taught Gemmeda and her four siblings that that education key to success.

After her father’s arrest, Gemmeda left for Yemen. She met her future husband in the refugee camp. He got a job in the camp’s Ethiopian restaurant, then she did. Over three years, she became the general manager.

When the lease expired, she won the bid to take over. “I knew everything, where to get it, how to cook, how to shop,” Gemmeda said.

The property owner chose Gemmeda for her business acumen. “I was competing with the people who have more money and in different businesses,” she said. “I took the highest risk to take that restaurant because I know how I can manage that restaurant.”

High risk meant operating in a place where businesswomen must temper assertiveness with caution. Yemen’s dominant conservative culture means women avoid confronting men publicly on issues large or small, offensive to the patriarchal society.

“At that time, this conservative Muslim country, so Yemeni ladies they don’t have rights there,” she said. “So it was hard for me to negotiate with so many of them, because they think that they don’t speak with a young lady.”

Her husband is soft-spoken, not a business negotiator. “He is not that kind of person,” Gemmeda said. “So I had to be strong there. There’s so many things going on there, but I make them to accept me like a man.”

Gemmeda found a way to negotiate the shoals and run the restaurant until her family could leave Yemen for the United States. She ran the restaurant to make money to send her son to English classes in Yemen. Zelalem was taking classes too, computer literacy lessons in a class provided by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

After the family arrived in Buffalo, Solomon took the Park School entrance examination and was given a full scholarship. He went on to obtain a bachelors in neuroscience at Colgate University, and is working in DC.

Gemmeda’s dream of a restaurant was crushed by the money it would take. Until a friend told her that the Westminster Economic Development Initiative was looking for restaurant operators who couldn’t afford a place of their own.

Abyssinia Ethiopian Cuisine opened with the original Grant Street site in 2011. After it was closed by fire, she shifted operations to Downtown Bazaar.

Where you can meet her on May 21, and she will greet you with coffee. At least now you know a little more about how far she came to serve you.

Ethiopian 101 is 5 p.m. May 21 at Downtown Bazaar, 617 Main St. Buy tickets, $35, here.

#30#